Archaeology

The federal sanctuary of Santa Vittoria covers an area of about 22 hectares, affecting the southwestern part of the Giara di Serri. The area, used in the Nuragic age for defensive purposes (as attested by the presence of a proto nuraghe and a tholos nuraghe), became-probably from the late Bronze Age/early Iron Age (12th-9th century B.C.-an important place of worship, where people from all over the surrounding area converged.

Reused for a long time and for different purposes, the area maintained its sacred destination even in the Christian era, as evidenced by the presence of a small church dedicated to St. Victoria, located on the edge of the jar, a short distance from the protonuraghe. The cult has remained alive over the centuries, in fact even today, on September 11 the local population goes to the plateau to participate in the celebrations in honor of the saint.

It was Antonio Taramelli, in the years between 1907 and 1929, who unearthed the archaeological site, bringing to light numerous Nuragic-age structures frequently reused for a long time.

After him, other archaeologists conducted excavations and studies on the sanctuary(E. Contu, M.A. Fadda, A. Saba, G. Paglietti, R. Cicilloni, J. A. Camara Serrano, L. Spanedda and N. Canu), and investigations are still ongoing by the Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio for the metropolitan city of Cagliari and the provinces of Oristano and South Sardinia.

The centerpiece of the sanctuary is the Nuragic temple dedicated to water worship. The monument is made of basalt blocks arranged in regular rows; it is surrounded by a temenos and consists of an atrium, a staircase and a chamber originally covered with tholos that contained lustral water.

The vestibule, equipped with benches, is crossed by a gutter where well water ran when it overflowed from the perfect trapezoidal staircase.

The walls of the shaft are preserved to a height of three meters, but by calculating their modest overhang we can assume an overall development of the tholos of no less than five meters.

Pilgrims who came to the shrine to participate in religious ceremonies often paid homage to the deities by donating objects of various kinds: pottery, perishable materials (probably first fruits, food offerings), and precious materials; these include amber necklaces and metal objects. Of particular note are bronze figurines (known as “Bronzetti”), depicting humans, animals or objects. Among the best-known ones found in Serri are the so-called chieftain, the “priestess,” the “mother with child,” as well as numerous specimens depicting bulls, doves, and foxes. The small bronzes found in Serri are currently on display in the National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari.

It is a structure with a rectangular plan, interpreted by Taramelli as a place of worship as a result of the presence of numerous bronzes; in reality, it is not clear to which deity it might have been dedicated, nor whether it was actually a temple, nor in which phase of the Nuragic age it was built: the only thing that is certain is that the building underwent several remodeling, as a careful observation of the structures shows.

The definition of “Ipetrale,” given by Taramelli following the discovery of a few boulders belonging to the roof, would indicate an open-air building; in fact, it is possible that the roof was made of perishable material or that-if, at least in part, in masonry-the stone material was reused to build other structures; in fact, after the Nuragics the area was frequented by Carthaginians, Romans, Byzantines, etc.

A short distance from the temples stand the remains of a nuraghe, evidence of the site’s original military vocation. In fact, the settlement developed-in the Middle Bronze Age (15th century BC)-around a protonuraghe, taking advantage of the high altitude of the Giara and the wide visibility over the surrounding territories.

During the Recent Bronze Age the fortification (which has since undergone several remodels) was replaced by a tholos nuraghe ; this probably had a complex plan, but at present only a few remains can be identified.

At the western end of the jar stands the small church dedicated to Saint Victoria. The first church (now no longer visible) was erected in Byzantine times by the garrison stationed there to control the territory. The present building, dating from the 17th century, is accessed through a round arch that was part of a now-demolished portico, of which remains, in addition to the aforementioned arch, a low wall placed in front of the entrance door to the rectangular hall that constitutes the present church.

Inside, four arches are preserved on the right side that allow, after recent restoration, the connection with the right aisle; while of those that certainly existed on the left side no clear trace remains as the wall has been covered with plaster. The church is consecrated and the feast, whose origin is connected with the renewal of contracts in the agro-pastoral sphere, takes place on September 11 with the processional accompaniment of the simulacrum of the Saint.

A Nuragic prototype of the Cumbessias, the festival enclosure was the space designated to welcome pilgrims to the sanctuary. The enclosure, with an elliptical plan (73×50 meters), is centered on the large central courtyard in which porticoed rooms and circular rooms face each other. There are two entrances to the enclosure: one to the southwest, the other to the southeast.

The porticoed space, covered by a single-pitched roof, offered pilgrims who came to the shrine a shelter in which to stay overnight and eat meals, perhaps prepared in the communal kitchen.

In addition to the porticoes, a number of huts are preserved; among them, the one known as the two-pronged axe is of considerable importance: in fact, a large bronze axe was found inside it, immaneled and hoisted on a small altar consisting of stacked stones, probably a cult object.

Adjacent to the axe hut nine small boxes, some equipped with slabs for the display and sale of goods, suggest that the enclosure was the place for exchanges both between the natives themselves and between Sardinians and outside merchants (Phoenicians, Estruscans and perhaps Greeks).

It is a structure with a circular plan, preceded by a probably double-sloped covered atrium. Unlike most Nuragic huts, characterized by a stone plinth and a conical roof of poles and branches, the temple in antis possesses high masonry walls, crowned probably by carefully shaped white limestone ashlars. It is possible that the peculiarity of the structure (which suggested to Taramelli its mistaken affiliation with a chieftain) is due to its function as a place of worship.

Inside, there are five niches with lintels and drainage window (intended to prevent the lintel from breaking); the lithic wedges used between the large basalt blocks are still visible.

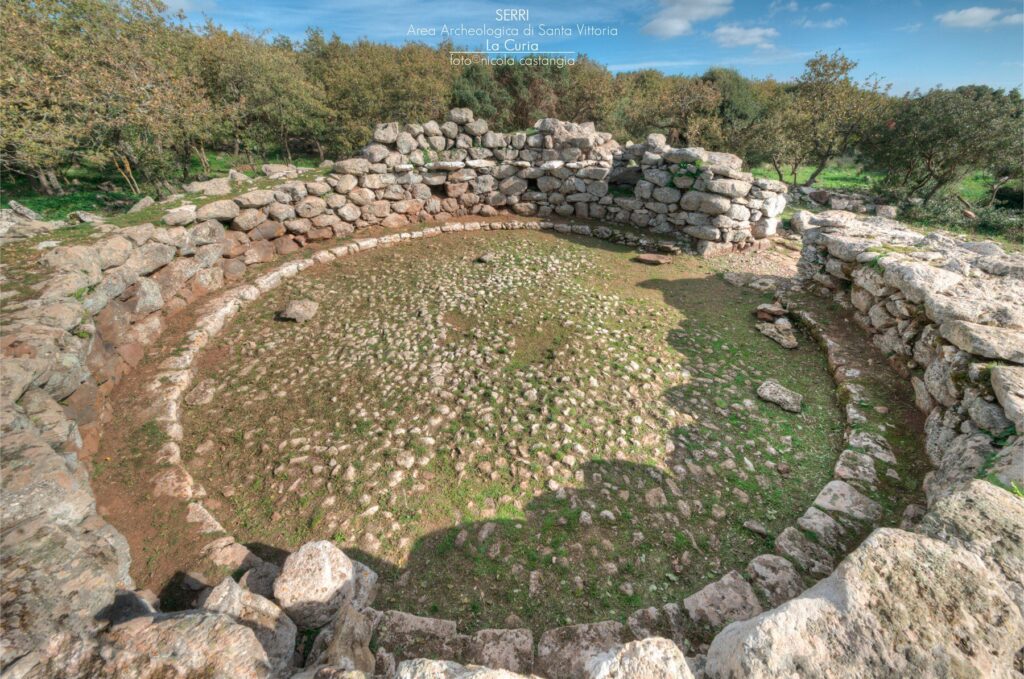

Another important building is the Curia or meeting hut, so called because of its size (14 meters in outside diameter) and because of the limestone seat that runs along the entire inner circumference. Inside, the large annular seat could seat more than 55 people, while the small basin and altar (still in situ today) document the practice of religious rites during meetings of the oligarchs.

The location of the building, the presence of the annular seat and the liturgical furnishings fundamental to Nuragic “parliaments” (Barumini-Su Nuraxi, Alghero-Nuraghe Palmavera, etc.) have led to the recognition here, too, of the hut of the Federal Assemblies “completely outside the architectural complex intended for the festivals, far from the noise of the latter, in the peace of the forest” (G. Lilliu).

In the small Parliament of Serri (meeting hall or Curia) the grave seniores of the Nuragic communities of the territories surrounding the jar of S. Vittoria convened; alliances were discussed, covenants were sworn, and these and those were sealed by a sacred ceremony that included animal sacrifices and liquid offerings (libations) or zoomorphic bronze statuettes.

The particular assemblies could also take place at night as would seem to be inferred from the Phoenician-Cypriot torchiere and the bronze shuttles, however, as noted by G. Lilliu, such artifacts could also relate to a liturgical norm that required a ‘burning flame, a symbol of light and divine splendor, a sign of clarity.

The dwellings.

At the northeastern end of the area is a series of dwellings with more or less complex floor plans; they are thought to have been the dwellings of those who resided permanently in the area.

The enclosure of the double betyle.

The block consists of a large central courtyard overlooked by seven rooms. The most important hut is the one called “of the double betyle” because of the presence of a kind of small altar composed of two stylized nuraghe towers (similar to those found at Monte Prama, Cabras), interpreted as an altar for the infilling of bronze ex-votos.

poi seleziona

poi seleziona